Former Owl Henry Burris part of CFL's 2020 Hall of Fame class

Henry Burris had tried to get his kids to keep a secret numerous times.

On one occasion, Burris had a birthday present stashed away for his wife, Nicole, but his sons, Armand and Barron, spoiled that.

But when the tables were turned and Nicole asked her sons to keep a secret from their father, she had them in check. Their lips remained sealed for nearly five months until some big news could finally be revealed.

In early July, Nicole asked Henry to come downstairs after breakfast and delivered the surprise of a lifetime. She told him to close his eyes, placed a pair of black Beats By Dre headphones on him, and a video started to play.

The video featured Damon Allen, a CFL Hall of Famer, and Mark DeNobile, the executive director of the Candian Football Hall of Fame. They were there to tell Burris he would be inducted into the CFL’s 2020 Hall of Fame class.

Burris was completely caught off guard by the news.

“I couldn’t hold back, I just let the tears flow,” said Burris, the former Temple quarterback who became the 21st player ever to enter the CFL’s Hall of Fame in their first year of eligibility. “To be able to enjoy that experience with my family, my wife, my two boys… it was the best way it could possibly be spent with the people that mean the most.”

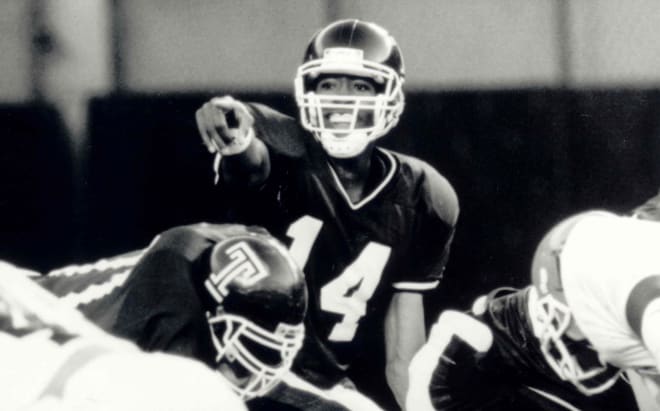

Burris played at Temple from 1993-96 and was inducted into the university’s athletics hall of fame in 2018. He finished his Owls career with 20 records and still owns the single-game mark for passing yards and total offense, which both came against Pitt in 1996.

Burris threw for 7,495 yards and 49 touchdowns on 558 completions and 1,138 attempts in college. Those marks were Temple records until former quarterback P.J. Walker surpassed them in 2016.

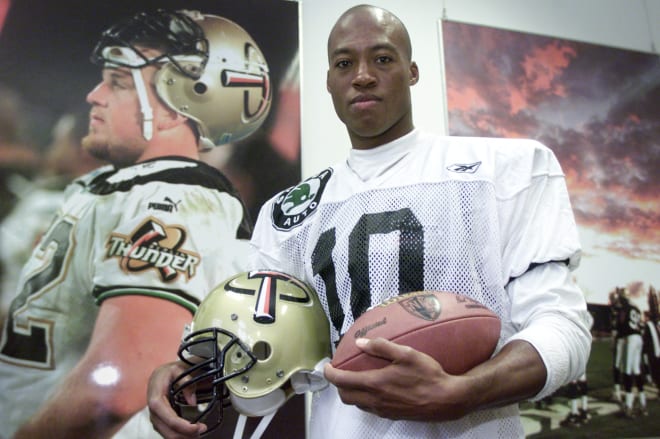

Burris had stints in the NFL with the Green Bay Packers, Chicago Bears and even saw time with NFL Europe's Berlin Thunder when the Bears assigned him there in 2003, but he rose to stardom in the CFL. He won three Grey Cup championships — two with the Calgary Stampeders and one with the Ottawa Redblacks. Burris also earned the CFL’s Most Outstanding Player Award twice and finished his career third in all-time CFL passing yards and passing touchdowns.

Burris is in Chicago now with the Bears as a training camp coach as part of the NFL’s Bill Walsh Diversity Coaching Fellowship.

“I’m so proud of him,” Nicole Burris said. “He can really just close the chapter. It’s complete and there’s just such a freeing feeling to that.”

Burris resides in Ottawa and works as a football analyst on The Sports Network (TSN) and a panel member on the network’s CFL on TSN broadcast.

But before he launched a broadcasting career, his professional football career in the NFL and CFL, and his time at Temple, he was a kid who lived on a nearly-600-acre farm in Spiro, Oklahoma, and flew under the radar of a lot of local schools when it came to his recruitment.

“Growing up on a farm taught me the necessities of life,” Burris said, “and that’s why coming to the big city for a country boy was all about getting used to the big city and the tall buildings. But outside of that, it was just another day of work.”

From the farm to the big city

In November of 1992, Temple ushered in what it hoped would be a new era of football with the hiring of Ron Dickerson as the team’s head coach.

Dickerson came from Clemson University as the defensive coordinator. He also coached cornerbacks at schools like Penn State, Colorado, Pittsburgh, Louisville and Kansas State.

Dickerson went to his Louisville connections to hire his offensive coordinator and quarterbacks coach, Steve Goldman, at Temple.

With the need for a quarterback in the Owls’ recruiting class, Goldman started churning through film of prospects inside the football offices at McGonigle Hall.

“When we got to Temple at that time it was not near the football program you have today,” Goldman said. “We played in the Big East, we got in there and we’re trying to find players to recruit… so we looked at a lot of film of quarterbacks all over the country.”

On one of his many late nights in the office, Goldman came across tape from a quarterback who went to Spiro High in Oklahoma. That quarterback was Burris.

“He was very well coached in high school,” Goldman said. “His fundamentals were really good for a kid coming out of high school.

“Quarterbacks have a lot of intangibles. It’s not only about throwing the ball. You have to have good leadership skills and Henry is a great person,” he added. “He comes from an outstanding family, his father and mother are wonderful people, and they instilled in this kid a great desire to succeed.”

John W. Montgomery, the offensive coordinator at Langston University at the time, sent the film to Dickerson because he believed Burris had a chance to play at the Division I level.

Montgomery was recruiting Burris to play for the Lions, but he did him a favor. He recognized Burris’ talent and brought Dickerson along with him for a visit to the Oklahoma native’s home.

Burris said the two sold him on the idea of playing against top schools in the Big East like Miami, Syracuse and Boston College, showcasing his talent on a big stage, and combining his ability to lead a team offensively with Dickerson calling the defense.

After the visit to Burris’ home, he agreed to take a visit to Temple’s campus and meet the rest of the coaching staff a few weeks later.

“For me, I was flattered,” Burris said. “I was like that girl that gets approached by that guy she’s always wanted to be with, or that guy that gets approached by that girl he’s always wanted to be with.”

On his visit, Burris really enjoyed Temple’s campus being within the city, but he said one of the main reasons he came to Temple was because of the conversations he had with Goldman. Goldman’s wealth of experience coaching the quarterback position at the collegiate and CFL level stood out to Burris.

While Goldman was in the CFL, he coached several quarterbacks that eventually went into the CFL Hall of Fame like Allen, Dieter Brock, Matt Dunigan, Tom Clements and Condredge Holloway.

“I was a big studier of professional quarterbacks and football, no matter what the greatest league was, and he had worked with some of the quarterbacks that I had ever seen play,” Burris said.

A few weeks after his visit to North Broad Street, Burris signed his National Letter of Intent and officially became an Owl, but Temple wasn’t really involved with his recruitment until after his senior season at Spiro.

Before his visit to Temple, Burris took a visit to Texas Tech, but the university was under investigation by the NCAA for several scandals, including recruiting, which scared him away.

Another school in the mix for Burris was Tulsa. The school was only about two hours from his house and he built a very good relationship with the offensive coordinator at the time, but he left for a job at Arkansas, which led to Burris seeking other options.

That’s when Dickerson and Goldman hopped in the picture. And after the visit to Temple, Burris respectfully declined other recruiting pitches that followed, even when Penn State’s recruiting coordinator called his father and tried to get him to visit Happy Valley.

“I was like, ‘OK, if you weren’t there this entire time, do you really want me?’” Burris said. “And I declined to take that visit because I didn’t want some team coming in at the last minute and thinking, ‘Oh, we’re the big fish here. We’re bigger than Temple. We can just come in and swoop this young kid up. Just knock him off his feet.’

“And even though it was appealing and I was flattered as heck, but still at that time… meeting Steve Goldman and Ron Dickerson and being there with a number of guys that ended up signing with Temple, I was just flattered by the overall experience of going to that school with the great history and also being in that city with so much history and so many things you can learn from and be involved in and have an opportunity to set me up for life outside of football as well. That’s what Temple offered.”

Chris Bunch, Burris football coach at Spiro, said Burris was under-recruited in high school due to his size. Burris only weighed about 150 pounds as a senior and some programs believed he wouldn’t be able to add muscle in college, despite the rocket he had for an arm.

“That really hurt him,” Bunch said of Burris’ size.

Temple also gave Burris an opportunity to turn around the football program, which was another part of their sales pitch to him during the recruiting visit to his home. When Burris enrolled as a freshman, the Owls had losing seasons in seven of their previous eight years.

During his visit in January of 1993, Burris walked around campus and McGonigle Hall thinking he could be one of the pieces of the puzzle to get the Temple football program to compete with some of the top schools in the Big East.

“I was thinking, ‘Man, this is going to be awesome when we go to this little closet of a weight room to having something big, like big-time like the other schools,’” Burris said. “I’ll be able to know that I’m one of the pioneers to help start this resurgence here on campus and put those types of facilities in place and get people excited to get involved with Temple football. Those were some of the things that motivated me to come to Temple.”

Unfortunately for Burris, it didn’t exactly go as planned on the football field.

Trying to rebuilding the program on North Broad Street

When Burris arrived at Temple in 1993, he was coming off a senior year of football where he was named the Oklahoma Offensive player of the year. And he played more than just football.

The eventual CFL Hall of Famer was quite the athlete at Sprio. Burris had four varsity letters in high school, including track, baseball, basketball and football.

In his junior year in 1991, Burris led Spiro to a 10-3 overall record and District championship until the Bulldogs were knocked out of the playoffs by Oologah High School.

Burris accepted the challenge to revitalize Temple’s football program, and he knew it wasn’t going to be easy. But he wasn’t able to translate the success he had in high school to the Owls, where they played in the Big East against steep competition and a tough non-conference schedule.

“If Henry could’ve played at every position, maybe we would’ve been OK,” Goldman said. “But it was a difficult time for Temple football.”

The Owls went a combined 5-39 in Burris’ four-year career at Temple.

In that era of Temple football, there was no football complex. The university didn’t pour resources into the program like it does today.

Edberg-Olson Hall, which resides on 10th and Diamond Street just off campus, didn’t exist. All of the athletics operations ran through McGonigle Hall. And sometimes the football and women’s lacrosse teams held practice at Geasey Field during the same time period, Burris said.

On top of that, the Owls played their home games at Veterans Stadium and Penn’s Franklin Field before sparse crowds and averaged less than 8,000 fans a game in three of Burris’ four seasons. Temple’s average attendance during the 1993 season was 7,712. In 1994, it was better but still not great at 15,623. And the 1994 total was helped by Penn State’s trip to Franklin Field, a game the Owls lost to the Nittany Lions, 48-21, as a 44 1/2-point underdog.

Burris helped steer a pair of early scoring drives in that game that produced a short-lived 6-0 lead, marking the first time Penn State had trailed in five weeks that season. But Temple just didn’t have the firepower or depth to keep up.

Dean Esposito, who eventually became one of Burris’ closest friends, was the Assistant Director of the Owl Club toward the end of Burris’ career at Temple. In his role, he raised money for the athletic department, assisted in corporate sponsorships and worked on the annual fund and preferred seating for the Liacouras Center, which was known as the Apollo at the time.

Another part of his job was to give away tickets for free in order to fill up seats. Esposito said the Owl Club would give him roughly 5,000 to 10,000 tickets every week to give to anyone who wanted them.

“Those games were brutal,” said Esposito, who had attended games since he was 5 years old. “It was like a morgue in those games. It was terrible. The atmosphere was terrible. I mean, tailgating? If there were 20 people tailgating, I’m telling you that was a lot. I’m not even kidding.”

While Burris enjoyed his time at Temple, he said it frustrated him that the football program wasn’t able to have any success during his career.

“I wish it would’ve been different,” Burris said. “It was frustrating going from the state of Oklahoma where you know how football is king and struggling, especially on the field athletically, to win games. And let’s be real, in a dormant stadium in Veterans Stadium at that time for Temple, so it was tough dealing with that. You always wondered, ‘Does anybody care?’ And it was frustrating.”

Meanwhile, Temple’s basketball program at the time was the hottest ticket on North Broad Street. Coached by future Hall of Famer John Chaney, the Owls were ranked as high as the No. 4 team in the country during Burris’ time at Temple. The Owls also made the NCAA Tournament every season.

Temple had stars on the basketball team like Eddie Jones, Aaron McKie — now the program’s head coach — and Rick Brunson. The trio all went on to have lengthy NBA careers.

Burris worked relentlessly with hopes of the football team one day getting the same recognition as the basketball team on campus. He looked at examples like Wisconsin and Northwestern — two schools that turned its football programs in the ‘90s — as the benchmark for Temple.

But Temple’s football program didn’t have sustained success like the basketball program until nearly 20 years after Burris’ career when the regimes of Al Golden, Steve Addazio and Matt Rhule called the shots for a program that had almost been cut by the university.

“We wanted to experience that same excitement,” Burris said, “that ESPN is coming to our school for our football game. But just unfortunately at that point in time, it never came. Of course I was happy for the basketball team, but there was a bit of jealousy in the background knowing, ‘Hey, we wanted that to be us.’”

Once his Temple career ended, Burris ranked second-all-time in Big East Conference passing yards with 7,495. He tossed 49 touchdowns to 45 interceptions and had a completion percentage of 49%. The Owls’ only conference win in that span came against Pitt in 1995, where they edged the Panthers, 29-27.

But Burris’ best season came during his sophomore year, when the Owls finished 2-9. He had 2,716 passing yards, 21 touchdowns and 12 interceptions. Burris also had his best single-season completion percentage that season at 52.6%.

Temple started off that season 2-1, which was the first time that happened since 1987 when Bruce Arians pushed the buttons for the program. After a Week 3 23-20 victory over Army, the Owls welcomed No. 4 Penn State, a team that eventually won the Rose Bowl, to that game at Franklin Field.

“The fact that we were able to win two of our first three games to kick off the season, people were excited,” Burris said. “They were wondering, ‘OK, is Temple for real? Or are they not?’

Again, Burris led two early scoring drives capped by two field goals by Rich Maston. But Penn State quickly countered, took a 27-12 halftime lead and didn’t look back in the second half.

Burris finished the game with 323 passing yards, the most by a Temple quarterback since 1971 at the time, in the 48-21 loss. His 10-yard touchdown pass to P.J. Cook cut Penn State’s lead to nine points in the first half.

“We played really way above our capabilities and Henry had a great day,” Goldman said. “He lit them up… they scored [48] but it was a much closer game than they anticipated.”

Burris said his favorite moment from that season came against Syracuse, then the 16th-ranked team in the country, midway through the season.

The Owls, staying at their usual spot at the DoubleTree Hotel in Center City on Broad Street, were preparing to head to meetings before the night game against the Orange. Burris and the rest of the team watched ESPN’s College Gameday to burn some time.

Lee Corso, who’s still a football analyst on the show, predicted Temple would give Syracuse a challenge, cover the spread, and possibly win outright. Immediately, Burris recalled, his whole floor erupted with excitement. His teammates started yelling, banging on walls and running down the hallway.

For a struggling program like Temple, getting any sort of positive mention on College Gameday was a plus, and it carried over into the game, even if getting there was an adventure in and of itself.

When it came time for the Owls to hop on the buses and head to Veterans Stadium, there was one problem: the buses never showed. The university somehow forgot to order the buses that usually take the football players and coaches from the hotel to the game, Goldman said, so the Owls had to improvise in order to get to South Philadelphia.

Luckily for Temple, public transportation in Philadelphia is easily accessible, especially in Center City.

Lee Roberts, the director of football operations at the time, bought everyone on the team subway tokens so they could ride the Broad Street Line to Veterans Stadium.

“We’re on the subway with people reading newspapers,” Goldman said. “They don’t even know there’s a game happening.”

Yet again, though, Temple fell short of Syracuse and lost, 49-42, to drop to 2-5 overall. Burris completed 32 of 53 passes for 392 yards and four touchdowns. The Owls trailed 42-14 early in the second half, but the offense erupted for 21 points in the fourth quarter.

Goldman said he told Dickerson jokingly after the game that the Owls should take the subway every game because they played so well.

“It would’ve been like when P.J. Walker and the gang beat Penn State in 2015,” Burris said of what it would have meant to beat Syracuse. “We would be experiencing that type of moment going into that game where we actually had a chance to beat one of the big fish on the block. The big bully on the block. Of course, unfortunately, it didn’t happen, but we were still primed for that moment. Just to hear the name and to receive that national notoriety was kind of a big moment for us.”

Temple went on to lose the rest of its games that season and finished the year 2-9 overall and 0-7 against Big East opponents.

“When we played that game against Kerry Collins and Penn State at Franklin Field that year, we actually felt that buzz of what it felt like for the basketball team playing UMass,” Burris said. “That was the one year I really felt that buzz, and it’s probably the most memorable year of my entire career at Temple.”

Some things are just meant to be

Burris, an Oklahoma native, had a lot of new experiences as a freshman at Temple. One of them was getting used to the big city after growing up on a farm his entire life.

Right after Burris got off the plane at Philadelphia International Airport, Temple’s recruiting coordinator, Chris LaSala, picked up him and some other players to head to campus. As the group drove north on I-95, Burris blurted out a line that some of his former teammates still joke about with him today.

“I looked outside of the window and I said, ‘Man, look at all of the big buildings,” Burris said. “And of course, country as can be when I said it, they all just started laughing… then when we got downtown I got and said, ‘Man, look at all these people.’”

Temple also offered activities and sports that Burris didn’t partake in down south, including lacrosse, so he started to attend games when he had time.

Burris said he genuinely enjoyed watching lacrosse because it was a combination of different sports formed into one. He found the concepts and strategies of the game interesting.

But one day in his senior year, he noticed a new player on the Temple women’s lacrosse team. It was freshman midfielder Nicole Ross, the woman he eventually married in 2004 nearly 10 years after seeing her for the first time.

“When she came on the scene, I really started going to lacrosse games,” Burris said jokingly. “Honestly, I would go to admire that fact that I never really had seen lacrosse. And to see a black girl out there be very successful in playing the game, I was enamored by that.”

And “very successful” might even be an understated descriptor for Ross’s lacrosse career. She was an All-American who helped the Owls compete deep in the NCAA Tournament. In 1997, Temple lost in the semifinals to eventual champion Maryland. Then, in 1998, the Owls fell to North Carolina in the quarterfinals.

Ross was named the Atlantic 10’s Offensive Player of the Year in 1999 as a senior when she scored 67 goals. Today, that ranks tied for fifth on Temple’s all-time list for goals in a single season. She also ranks third all-time in ground balls with 166.

Up until recently when Burris got the news of the CFL nod, Nicole Burris would joke with her husband and tell him she was the best athlete of the family.

“I have to now finally concede,” Nicole said. “He’s literally the oldest professional quarterback to win a championship in the world. Like, what am I going to do with that? I’m done. I was done at 21.”

Even though Burris first saw his future wife at her games at Geasey Field, he didn’t actually meet her in person until they ran into each other in the athletic therapy room. Back then, Temple didn’t have the facilities it had today, so lots of the athletes shared spaces in McGonigle Hall.

Nicole was shocked they didn’t bump into each other more than they did, but after their first conversation, they became friends and started to date.

“Our friendship just grew into something more over the years,” Burris said. “And when I left, that was always a challenge, but we always stayed in touch and now the rest is history.”

Like her husband, Nicole Burris didn’t initially have Temple high on her list when it came to her recruitment. When she was a senior at Arundel High in Gambrills, Maryland, a coach on the junior varsity team went to a lacrosse coaching clinic at Temple. Once the coach returned to Arundel, she told Nicole that she wanted to put together a highlight to send to the Owls with hope of helping her land a spot on a college roster.

And it worked.

“Temple wasn’t on my radar and it wasn’t on (Henry’s) radar either,” Nicole Burris said. “So we reflect on it all of the time and we’re very grateful.”

‘He’s a Temple guy’

Burris still has a long time to think about what he’s going to say when he’s inducted in the CFL Hall of Fame. With the coronavirus pandemic spreading worldwide, the CFL has decided to postpone the enshrinement until the following year with the 2021 class.

Burris said he understands the moment and is remaining patient until 2021 so he can celebrate the right way next year with friends and family.

“I don’t want to social distance when we’re smoking cigars and enjoying a scotch and celebrating the moment,” Burris said. “I want to make sure we’re right up on each other, toasting to the moment, screaming, reminiscing about things, and just having a great time without any inhibitions.”

As Burris watched the video that informed him of his induction into the CFL Hall of Fame, his whole career flashed before his eyes.

His time at Spiro High in Oklahoma where he had a cannon of an arm, but didn’t garner the attention of big-time programs? He saw that. Then, to his time at Temple where he juggled the life of a student athlete and went to war with a subpar cast of players around him? He saw that, too. And finally, his stints in the NFL and then to his decorated career in the CFL, where he battled adversity, injuries, and franchises that lost faith in him? You better believe he saw all of that.

“A lot of people didn’t think he was going to make it,” Bunch said. “But he proved them all wrong.”

And throughout every step of his career, he brought a piece of what he learned at Temple with him. Now, it has a spot in the CFL Hall of Fame.

“It’s going to be a hell of a celebration,” Esposito said. “It’s nice also that he’s a Temple guy. It’s one of ours. Obviously, he’s my best friend, but it’s one of our guys. He’s a Temple guy and that really means a lot to Henry and myself, I know that for a fact. And Nicole, for sure. We’re all Temple people.”